Lander has a very special place in my heart, and I have always longed to know how it works. Back in 1989 I was lucky enough to upgrade my trusty BBC Micro to an Archimedes A410/1, and I still look back on my first ARM-powered machine with a deep kind of awe. I fell in love with my Arc, more than any machine before or since, and Lander had an awful lot to do with it.

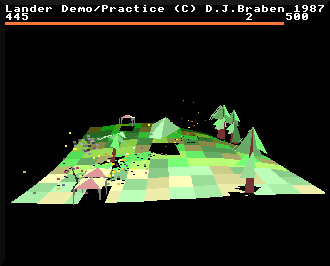

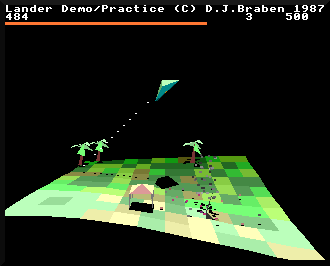

I can still remember the anticipation of double-clicking on the !Lander application for the first time, and being completely awestruck by the vibrant 3D landscape that appeared. Sure, I nudged the mouse and my ship exploded, and the game proved to be frighteningly difficult to play to any extent, but this was the same rite of passage that every single owner of a new Archimedes would go through, and I bet most of us remember it fondly. Lander is a tantalising combination of wonder and near-instant death, and it still blows me away today, not because it's an amazing game (it isn't, if I'm going to be brutally honest), but because it's just so achingly beautiful.

It also helped that Lander was "what David Braben did next". I'd spent a worryingly large portion of the preceding years playing Elite, the epic BBC Micro game that Braben co-wrote with Ian Bell, and although I'd read about Lander and the commercial game that it spawned, Zarch, I'd only seen static screenshots in magazines. Watching the gentle hills pass by beneath my ship, with pretty fir trees and quaint gazebos lining the warm blue shores, I felt transported. I was entranced enough to buy Zarch, which was technically even more impressive, but somehow Zarch didn't captivate me in the way that its calmer predecessor did; even now I prefer Lander to Zarch, even though it still kills me the second I grab the mouse.

So having already disassembled and documented three of the most iconic BBC Micro games - Bell and Braben's Elite, and Geoff Crammond's Aviator and Revs - I just had to tackle Lander. I'm so glad I did, as it turns out that not only is Lander still a beautiful game to play, it's even more beautiful on the inside, despite - or perhaps because of - its hasty inception.

Braben famously wrote Lander in around two months, starting his work on an ARM1-based ARM Evaluation System that was hooked up to a BBC Micro as a second processor, before getting his hands on a prototype Archimedes A500 in early 1987. As a result the code feels almost minimalistic. There's practically no cruft, there's no hard-to-follow code that's been twisted for efficiency's sake, and instead there's the landscape and the player and the particle system and the mouse-based controls... and not a great deal else. It's very zen, not least because the ARM1 instruction set that Braben ended up using is, by design, simplicity itself; there are no MUL instructions anywhere in Lander, as the latter only appeared on the ARM2 in the A500, so this is not only the first ARM game ever written, it's quite possibly the only game ever written for the first version of the ARM chip. Given how the ARM processor powers an awful lot of the modern world, that's quite something.

Going from Elite to Lander is also a fascinating process, as Lander owes a lot to its predecessor. For example, each 3D object in Lander is defined using an object data block, and the format of this block is a familiar one. Elite defines its wireframes using vertices, edges and faces, and Lander defines its 3D objects using the exact same approach, though it only needs vertices and faces, as edges aren't needed for filled 3D graphics. And when drawing these objects, the same backface-culling methods are used as in Elite, except this time the results of the calculations feed into the colours used to draw the faces, giving Lander a solid, three-dimensional look that makes the most of the 256-colour mode it runs in.

Not only that, but the object routines use the same orientation vector-based rotation matrices (just updated to an easier-to-follow right-hand coordinate system). It's all familiar stuff, not surprisingly given the development timescales.

And, of course, Braben just had to continue honing his mastery of procedural generation, as the landscape in Lander isn't stored anywhere but is generated on-the-fly, using a fast but effective Fourier-based synthesis to calculate the altitude of each point on the landscape as it's required. Elite had to fit into the BBC Micro's 32K of memory and Lander had to fit into the Archimedes A305's 512K, and in both cases, very clever maths comes to the rescue.

Lander is David Braben's second moment of genius, coming straight after the whirlwind of Elite's storied development. It is an absolutely monumental achievement to have created this classic in just two months - and on a brand new CPU architecture, to boot - and I hope you enjoy reading through his wonderful code as much as I have enjoyed exploring it.