Drawing 3D objects using object blueprints and rotation matrices

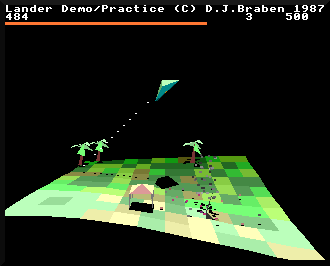

As discussed in the deep dive on object blueprints, Lander defines 13 object designs (though one is unused). Each object has an object blueprint that contains details of the object's shape and characteristics. In this article, we're going to talk about how Lander takes an object blueprint and draws a 3D object on the screen, like this scene, where the player's ship, gazebo, trees and smoking remains are all 3D objects:

We'll also cover object shadows, which are an important part of the three-dimensional routines, giving objects like the player's ship and the gazebo in the above a real sense of presence.

Drawing 3D objects

------------------

There are quite a few subroutines that control how objects are drawn. They are as follows:

- The DrawObjects routine is responsible for drawing objects that sit on the landscape. It is called directly from the main loop on each iteration, and it works through all the objects on the object map, looking for those that are visible, and deciding which blueprint to draw for each object. It then converts the 3D coordinates of those objects into camera-relative coordinates, ready to be passed to the DrawObject routine. See the deep dive on placing objects on the map for more about the object map, and the deep dive on the camera and the landscape offset for more about camera-relative coordinates.

- The DrawObject routine draws a single 3D object, as well as its shadow (if the object blueprint says it should have one). The routine draws the object and its shadow into the graphics buffers, so that they can be drawn on-screen at the correct depth later on in the main loop. See the deep dive on depth-sorting with the graphics buffers for details.

- The MoveAndDrawPlayer routine is responsible for drawing the player's ship into the graphics buffers. It does this by calling the DrawObject routine to draw the object, after calculating the correct rotation matrix for the ship's orientation.

- The DropARockFromTheSky routine is responsible for drawing falling rocks. Even though rocks appear on-screen as 3D objects, they are actually implemented as a special type of particle, and the rock-drawing code appears in part 3 of the MoveAndDrawParticles routine, which then calls DrawObject to draw the rock.

As you can see, all of these approaches end up calling the DrawObject routine to draw the relevant object into the graphics buffers, so let's take a closer look at how this works.

The DrawObject routine

----------------------

The DrawObject routine is called with the camera-relative coordinates of the object in (R0, R1, R2), and the address of the object's rotation matrix in R3. Camera-relative means they are relative to the player's coordinates, rather than the 3D world, which is what we need to work with when drawing on-screen (see the deep dive on the camera and the landscape offset for more about camera-relative coordinates).

We'll look at the rotation matrix in more detail below, but most objects are static and simply ignore the rotation matrix; for example, trees, rockets and buildings always face the same way and don't rotate, so they are static objects and ignore the rotation matrix entirely. The only objects that rotate are the player's ship and falling rocks, which we'll look at in more detail in a later section.

We'll also look at the shadow calculations in more detail in the next section, but for now, this is what DrawObject does when drawing a 3D object (you can click the links to see the relevant part of the code):

- Part 1 of 5: Scale up the object's coordinates

- Copy the object's camera-relative coordinates into (xObject, yObject, zObject)

- Scale the object's coordinates as large as possible without losing any data and store them in (xObjectScaled, yObjectScaled, zObjectScaled)

- Set crashedFlag = 0 to indicate that the object has not crashed (though we will change this later if we find that it has)

- Part 2 of 5: Process the object's vertices

- For each of the vertices in the object's blueprint, do the following:

- If this object is static, add the vertex coordinate to the object's camera-relative coordinate; the vertex coordinate is relative to the centre of the object, so this gets us the camera-relative coordinate of the vertex

- If this object is rotating, apply the rotation matrix to the vertex coordinate first, which rotates the object to its correct orientation, and then add the rotated vertex coordinate to the object's camera-relative coordinate; this gets us the camera-relative coordinate of the vertex with the object rotated to the correct orientation

- Project the coordinate onto the screen, saving the results in the vertexProjected table (see the deep dive on projecting onto the screen for details)

- Calculate the altitude of the landscape directly below the vertex, which gives us the coordinate of the shadow for this vertex (see below for more on this)

- Project the 3D shadow coordinate onto the screen, saving the results in the vertexProjected table

- If the shadow vertex appears higher up the screen than the corresponding object vertex, then we know the object has hit the ground, so set crashedFlag = &FF to indicate a crash

- Repeat the above until we have projected all the object vertices and their shadows

- For each of the vertices in the object's blueprint, do the following:

- Part 3 of 5: Calculate the visibility of each of the object's faces

- For each of the face definitions in the object blueprint we now loop through parts 3 to 5, so do the following:

- Fetch the face normal vector from the ship blueprint (so this is a vector that points perpendicularly out of the face)

- If this object is rotating, apply the rotation matrix to the normal vector, so this gives us the normal vector for this face with the object rotated to the correct orientation

- If this object is static, then all faces are always visible and they always cast shadows, so we set various flags to record this

- If this object is rotating, calculate the dot product of the rotated normal vector and the object's scaled camera-relative coordinates in (xObjectScaled, yObjectScaled, zObjectScaled), to give us a value that determines whether the face is visible, so we can skip drawing the face in part 5 if applicable (see below for more on this calculation)

- For each of the face definitions in the object blueprint we now loop through parts 3 to 5, so do the following:

- Part 4 of 5: Draw the shadow for each of the object's faces

- Still working through each of the face definitions in the object blueprint, do the following:

- If the object is configured not to have a shadow (bit 1 of objectFlags is clear), jump to the next part, otherwise keep going to draw this face's shadow on the ground

- If this object is rotating then we only draw shadows for faces that point upwards, so check the y-coordinate of the rotated face normal to see which direction the face is pointing, and if it is pointing down, jump to the next part to skip drawing the shadow

- Fetch the shadow's projected coordinates from the vertexProjected table, which we calculated in part 2

- Fetch the three vertex numbers for this face from the object blueprint

- Draw the shadow in black into the graphics buffers by calling the DrawTriangleShadowToBuffer routine, passing it the projected shadow coordinates for the three vertex numbers we just fetched

- Still working through each of the face definitions in the object blueprint, do the following:

- Part 5 of 5: Draw each of the object's faces

- Still working through each of the face definitions in the object blueprint, do the following:

- If the face is not visible (which will only be the case if the object is rotating and the face is pointing away from the camera), skip the following to move on to the next face

- We now calculate the colour of the face to draw, which we start by fetching the face colour from the object blueprint, in the form &rgb

- Calculate a brightness value that depends on the (potentially rotated) face normal's y-coordinate, so the brightness is larger when the face is pointing more directly upwards (as then it gets more light on it, as the light source is above us)

- Tweak the brightness level depending on the (potentially rotated) face normal's x-coordinate, to simulate the light source being slightly to the left

- Build a VIDC colour word from the &rgb colour and the brightness level (see the deep dive on screen memory in the Archimedes for more about this)

- Fetch the three vertex numbers for this face from the object blueprint

- Draw the face into the graphics buffers by calling the DrawTriangleToBuffer routine, passing it the projected coordinates for the three vertex numbers we just fetched, and setting the colour to the correct colour and brightness level

- Loop back to part 3 to draw the next face, until we are done

- Still working through each of the face definitions in the object blueprint, do the following:

For those who are familiar with the way Elite draws its 3D ships, the above process is not unfamiliar, as Elite also uses vertices and face normals to define its objects (though it also defines edges, which are used to draw the famous wireframes - something we don't need to do here). You might like to compare the above to the process with that for drawing ships in Elite - parts 5 to 8 of Elite's LL9 ship-drawing routine are pretty similar in structure to the routines in Lander.

There is another consequence of using the same drawing approach as Elite. Rotating objects have to be convex and fully closed, as otherwise the calculation would flag faces as being visible when they might be hidden by the rest of the object. The rotating objects in Lander are all convex - the ship, rock and pyramid - so this works. Static objects like the trees and gazebos do not have to follow this rule, as all their faces are always drawn; instead, the faces in their object blueprints are ordered so the faces at the back of the object are drawn before the faces at the front. If we tried to rotate a static object, it wouldn't look correct, as only convex and fully closed objects work with this approach. There are no rotating gazebos in Lander...

Drawing object shadows

----------------------

The above process draws both the object and its shadow on the ground. The shadow is calculated in a very simple manner that isn't perfect, but even when you know about its shortcomings, it's still convincing enough to give a really solid feeling to the three-dimensional world.

Given a face and its camera-relative coordinates, we can calculate the coordinates of its shadow by simply projecting that face directly down onto the landscape, as if a bright light were shining from directly above the object. This is a quick calculation, but there are two disadvantages: one, the shadow doesn't drape properly over the landscape as it's a 2D plane rather than a proper 3D object (so although each vertex is at the correct altitude, the result is more like a sheet-metal shadow than a cotton-blanket drape); and two, we ignore objects on the ground, so the shadow will appear beneath an object like a gazebo, and not on the top of the object. In practice, this doesn't really matter, and the effectiveness of the shadow far outweighs any real-world inaccuracies.

As for the calculation, we already have the coordinates of each of the face's vertices, so we can get the altitude of the point directly under each vertex by calling the GetLandscapeBelowVertex routine. This routine converts our camera-relative coordinate into a 3D world coordinate, and we can then pass the x- and z-coordinates of the vertex to the GetLandscapeAltitude to calculate the altitude of the landscape directly below the vertex (see the deep dive on generating the landscape for details).

We then use the result as the y-coordinate of this vertex's shadow coordinate, with the added bonus that we can also do a quick check against the vertex's object coordinate to see if the shadow is higher than the object, in which case we know that the object has hit the ground. This isn't much use for static objects, but it's very useful for the player's ship.

Rotating objects

----------------

In the above we glossed over a very important aspect of the drawing process - the rotation matrix. Most objects don't take any notice of the rotation matrix, but objects that have bit 0 of their object flags set are rotating objects, and that adds another layer to the drawing process. There are only three rotating objects in Lander - the player's ship, rocks and the unused pyramid object - but Lander's successor Zarch contains lots of rotating objects, and they're all based on the same system of rotation matrices.

A rotation matrix is a way of defining a rotation in 3D space. We can therefore use a rotation matrix to define an object's orientation in space (the rotation matrix is what we apply to an object coordinate to rotate it to the correct orientation). Rotation matrices can also be thought of as consisting of three vectors, each of which points along one axis of the object - out of the object's nose, out of the object's roof and out of the object's right side.

The rotation metrices in Lander can therefore be thought of like this:

[ xNoseV xRoofV xSideV ] [ yNoseV yRoofV ySideV ] [ zNoseV zRoofV zSideV ]

where the nose, roof and side vectors are the orientation vectors.

In Lander there are only two rotation matrices. One defines the orientation of the player's ship, and is calculated in the MoveAndDrawPlayer routine (see the deep dive on flying by mouse for more on this). The other rotation matrix follows the progress of the main loop counter, and gently spins around two axes (see the deep dive on the main game loop for details); this latter matrix gets applied to any falling rocks to give them a slow rotation effect as they fall.

For the purposes of this article, the rotation matrix enables us to rotate the player's ship and rock objects so they have the correct orientation; see the deep dive on flying by mouse for more information about how the rotation matrices work.

Dot product

-----------

In part 3 of the DrawObject routine, we use the dot product to work out whether or not a face in a rotating object is visible. Let's take a look at that calculation.

The dot product is calculated by the GetDotProduct routine. This takes two vectors at R0 and R2 and calculates the dot product in R3 as follows:

[ R0 ] [ R2 ]

R3 = [ R0+4 ] . [ R2+4 ] = (R0 * R2) + (R0+4 * R2+4) + (R0+8 * R2*8)

[ R0+8 ] [ R2+8 ]

The dot product of two vectors gives us a value that depends on the angle between the two vectors. In the case of DrawObject, we calculate the dot product of the rotated normal vector and the object's camera-relative coordinates, like this:

[ xNormal ] [ xObjectScaled ]

R3 = [ yNormal ] . [ yObjectScaled ]

[ zNormal ] [ zObjectScaled ]

The sign of the dot product depends on the angle between the two vectors, so R3 is:

- Negative if angle < 90 degrees

- Positive if angle >= 90 degrees

The vector at xObjectScaled is the vector from the camera to the object, so we can see faces with normals that are less than 90 degrees off this vector, as they point towards the camera, while hidden faces point away from the camera at angles of more than 90 degrees.

So if R3 is positive, the face is facing away from us and is not visible, and if it's negative, the opposite is true.

It's worth noting that the dot product result is not used to determine the brightness of the face, as the light source is at a fixed position above the scene and slightly to the left. This means we only need to use the rotated normal to work out the face brightness. If the light source were at the camera, then the dot product would come in handy, but having a light source above everything makes things a bit easier, while also fitting in with the object's shadows appearing on the ground.