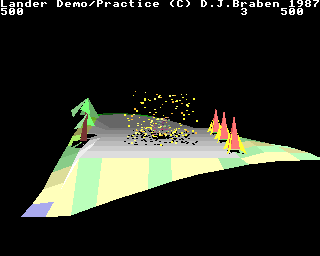

Flying the ship in Lander using polar coordinates and thrust vectors

Lander might be famous for its smooth 3D landscape and mind-blowingly smooth graphics, but it's infamous for something quite different. You play the entire game using nothing but the Archimedes' three-button mouse, and although I am assured that after a lot of practice this control scheme makes flying the ship intuitive and very fine-controlled, I suspect I am not alone in thinking that perhaps the controls are just a bit too difficult for us more casual gamers to master.

Luckily, understanding how the control scheme works does make life a bit easier, so in this deep dive we'll look at how the mouse position is converted into polar coordinates, and what those coordinates mean when flying our ship.

Find the centre point

---------------------

The key to understanding Lander's control scheme is to ignore the advice given in the application guide. "Manoeuvre [the ship] by turning the mouse slightly to the right or left, towards you or away from you," it says. "Keep the [ship] moving by turning the mouse to tilt it," it goes on.

I might not know a lot, but I do know that you don't "turn" a mouse, even a fancy three-button mouse like the one that comes with the Archimedes. Luckily the manual for Zarch is way better at explaining how the control scheme works, but this site is about Lander, not Zarch, and on this score the manual should hang its head in shame. Just ignore it - this is bad advice, and it is poorly worded.

The way the controls actually work is both ridiculously simple and ridiculously complex. When we start from the launchpad, the position of the mouse is set as the "centre point". If we move the mouse away from the centre point, then the ship tilts forwards in the direction that we are moving. The further we move the mouse away from the centre point, the greater the amount that the ship tips forwards - and if we keep moving the pointer away from the centre point, the ship will tilt so far forwards that it starts to point towards the ground.

Moving the mouse back to the centre point will bring the ship back to a level position (though moving it exactly to the centre point will make it very difficult to control the direction, so don't be too accurate when moving it back). This is the key thing to remember about Lander: try to remember where the centre point is on your mouse mat, and always move with this point in mind. If you lose track of the centre point, then you'll lose track of your ship's tilt, and that's almost certainly going to cause difficulties (though it's not too hard to find the centre again through trial and error, if you're high enough off the ground).

Now that we have the basics of the control scheme, let's look at the maths behind the controls.

Polar coordinates

-----------------

Of course the control scheme is mathematical - this is David Braben we're talking about here. Specifically, the controls are based on the concept of polar coordinates, which is something we all learned about at school, and then promptly forgot.

Most coordinates we deal with in Lander are Cartesian coordinates - these are typically the 3D coordinates of the (x, y, z) variety, or screen coordinates of the (x, y) variety, with each coordinate giving the distance of the point along one of the orthogonal axes. Polar coordinates don't describe locations using the traditional axes, but instead they define a location in terms of an origin, an angle and a distance. In the two dimensions of the mouse mat, the origin is the "centre point" we talked about earlier, the angle is the direction in which we move the mouse, and the distance is measured between the origin and the mouse position.

To explain this, let's imagine that we start the game with the mouse in the middle of our mouse mat, and we move the mouse up and right from the centre point. The mouse mat then looks a bit like this:

+------------------------------------------------------+ | | | + <- mouse | | position | | | | | | + | | ^ | | | | | centre point | | | | BEEBUG | +------------------------------------------------------+

As you can see, our mouse mat was supplied by BEEBUG. That's who I bought my Archimedes from, as well as my trusty copies of Zarch and Conqueror. I loved that mouse mat. I literally wore it out. Happy, happy days...

Anyway, coming back to Lander, we can consider this mouse position in terms of polar coordinates, with the origin at the centre point. The distance part of the polar coordinate is the distance between the mouse position and the origin, and we measure the angle from the horizontal, as follows:

+------------------------------------------------------+ | | | + | | .´ | | distance --> .´ | | .´ \ <- angle | | +´----`-------- | | | | | | | | | | BEEBUG | +------------------------------------------------------+

The GetMouseInPolarCoordinates routine is responsible for converting the mouse position into a polar distance and a polar angle. It does this by using arctangents and Pythagoras, which sounds complicated but is relatively straightforward. The routine takes the mouse's x- and y-coordinates and creates a triangle that looks like this:

+------------------------------------------------------+ | | | + | | .´| | | .´ | y | | .´ | | | +´------+ | | x | | | | | | | | BEEBUG | +------------------------------------------------------+

(It also makes both coordinates positive, but we'll come back to that in a minute.)

Taking the angle in the bottom-left corner of the triangle, trigonometry tells us that the following is true:

tan(angle) = opposite / adjacent

= y / x

So it follows that:

angle = arctan(y / x)

So GetMouseInPolarCoordinates calculates the angle we want using an arctan lookup table at arctanTable.

Meanwhile, if we want to find the distance along the diagonal side of the triangle, Pythagoras tells us that the following is true:

distance^2 = x^2 + y^2

So it follows that:

distance = SQRT(x^2 + y^2)

where SQRT is the square root function. So GetMouseInPolarCoordinates calculates the distance we want using a square root lookup table at squareRootTable.

The final step is to check the original signs of x and y from before we made them positive, and then add the correct amount to the angle so that it points in the right direction... and that's how we can convert the mouse position into polar coordinates.

This process is managed by part 1 of the MoveAndDrawPlayer routine, where there is quite a bit of maths around scaling the mouse coordinates to ensure an accurate result, and capping of the polar coordinates to ensure they don't get out of range. This scales the polar distance into an angle that we can use to define the ship's forward pitch (with a larger distance giving us a steeper angle), and we then use this pitch angle and the original polar direction angle to update the ship's current pitch and direction in the shipPitch and shipDirection variables.

We don't just replace the old figures with the new ones, however. Instead there is an element of damping to make the ship more controllable, which is applied like this:

newPitch = shipPitch - (shipPitch - distance) / 2 newDirection = shipDirection - (shipDirection - angle) / 2

Removing this damping makes the ship instantly responsive, which makes it a lot harder to control, so it's an important part of the control scheme.

So the above process converts the mouse movements into polar coordinates, and we then use those polar coordinates to determine the direction and angle of the ship's pitch. And what do we do with these figures? More maths, of course.

The ship's rotation matrix

--------------------------

In order to apply the direction and angle of the ship's pitch to the actual ship in 3D space, we need to convert these figures into a rotation matrix.

The CalculateRotationMatrix routine does exactly this. It takes two rotation angles as arguments - in this case, shipPitch and shipDirection - and composes a rotation matrix that describes the following rotation:

- Spin the ship around on its base until it is facing in the direction of the shipDirection angle

- Pitch the ship forwards by the shipPitch angle

If a is the shipPitch angle and b is the shipDirection angle, then the resulting rotation matrix looks like this:

[ cos(a) * cos(b) -sin(a) * cos(b) sin(b) ] [ sin(a) cos(a) 0 ] [ -cos(a) * sin(b) sin(a) * sin(b) cos(b) ]

This matrix can be derived using simple trigonometry; for an example, check out the deep dive on pitching and rolling in my Elite project (the maths in Lander is slightly different as Elite pitches and rolls while Lander pitches and yaws, and Elite uses a left-hand coordinate system while Lander uses a right-hand system, but the principle is the same).

As this is a rotation matrix, it can also be written in the following form:

[ xNoseV xRoofV xSideV ] [ yNoseV yRoofV ySideV ] [ zNoseV zRoofV zSideV ]

The rotation matrix is used for a few things. The most obvious to the player is the DrawObject routine, which takes the address of a rotation matrix as an argument. When drawing the player's ship in part 3 of the MoveAndDrawPlayer routine, we pass in the ship's rotation matrix, so the ship gets drawn with the correct orientation. The only other rotation matrix in the game is for the rocks, which tumble as they fall from the sky. This tumbling motion is implemented by a rotation matrix whose angles are dependent on the main loop counter; see the deep dive on the main game loop for details.

The individual orientation vectors in the ship's rotation matrix are useful too. For example, the nose vector is used to determine the direction of bullets that are fired from the ship's gun, which points out of the front of the ship, in the same direction as the nose vector; see the deep dive on collisions and bullets for details. And because the roof vector points out of the bottom of the ship, it can be used to determine the direction of thrust and the shape of the exhaust plume.

Thrust is a pretty important aspect of flying by mouse, so let's look at that first, before moving on to the exhaust plume.

Applying thrust

---------------

Pressing the left mouse button fires the ship's engines at full speed, while pressing the middle button engages hover mode, where the engine fires at a lower power. Both buttons activate the engine on the bottom of the ship, pushing an exhaust plume out of the ship's undercarriage and propelling the ship in the opposite direction.

The first step in applying thrust is in part 1 of the MoveAndDrawPlayer routine, where we scan the mouse buttons and store the results as a thrust level in the fuelBurnRate variable. This variable simply stores the state of the mouse buttons as returned by the OS_Mouse operating system call, so bit 0 stores the state of the fire button, bit 1 the state of the hover button, and bit 2 the state of the thrust button (with a set bit indicating that the button is being pressed). Bit 0 of the fuel rate is ignored in the fuel consumption calculations, so firing bullets does not burn fuel, even though bit 0 of fuelBurnRate is set.

With fuelBurnRate set to the correct thrust level, we move on to part 2 of MoveAndDrawPlayer, where we update the player's velocity and coordinates according to the thrust we're applying. First, though, we do an altitude check on the player, and if they are above the level defined in HIGHEST_ALTITUDE, we stop the engines from firing by clearing bits 1 and 2 of fuelBurnRate, as the ship is too high for the engines to work.

We then fetch the following:

- The player's current coordinate from [xPlayer yPlayer zPlayer]

- The player's current velocity vector from [xVelocity yVelocity zVelocity]

- The ship's roof vector from [xRoofV yRoofV zRoofV], which we store in a new vector called [xExhaust yExhaust zExhaust], which is the vector that points in the direction that the exhaust plume travels (so the thrust that is delivered is in the opposite direction)

Once we have all the information we need, we work through each axis in turn, doing the following:

- First we reduce the velocity vector along each axis by 1/64, to simulate friction (so our ship will slow down naturally if we don't apply thrust).

- Next we check whether full thrust is being applied (left button), and if it is we subtract each axis of the exhaust vector (divided by 2048) from the relevant axis of the velocity vector. We subtract the exhaust vector to apply thrust because the direction of the thrust applied by the plume is in the opposite direction to the plume itself (in other words, a rocket's plume pushes downwards so the rocket can rise up). So this applies the full thrust from the engine to the ship.

- Then we apply the player's velocity vector to the player's coordinates, so the player moves through space in the correct direction and speed.

- Next, if hover mode is engaged (middle button), then we apply a quarter of the full thrust vector to the velocity, rather than the full thrust vector we apply for the left button.

- Finally we store the updated player coordinates and velocity.

Note that the hover thrust is applied after we apply the velocity vector to the player's coordinates, so hovering has a slightly delayed impact on the ship, to simulate the effects of inertia.

Now that we've applied thrust to the ship's movement, the final step is to draw a fancy exhaust plume, so the player can work out exactly where the thrust is being applied. Let's look at that now.

Drawing the exhaust plume

-------------------------

The exhaust plume is made up of exhaust particles. The deep dive on particles and particle clouds explains how exhaust particles are added to the particle data buffer and how they behave, but for our purposes here, they are particles that fade from white to red over their lifespan, splash on impact with water, bounce on impact with the ground, and have gravity applied to them. They have a default lifespan of eight iterations with a random element of 0 to 8, and they have a random velocity range of -&400000 to +&400000. This is all explained in more detail in the particle deep dive.

The exhaust plume is added in part 4 of MoveAndDrawPlayer, which adds two particles if hover mode is engaged, or eight particles if the engine is at full thrust. As this routine is called on every iteration around the main loop and the default lifespan of each particle is eight iterations, that means the plume has a minimum of 64 particles when the engine is fully engaged, with that number rising depending on the random element that gets added to the lifespan of each particle.

All that remains is that we set the initial coordinates and velocity vector for each of the plume particles. We apply the same values to all of the particles that are spawned in each iteration, as follows.

First we fetch the exhaust vector [xExhaust yExhaust zExhaust]. This tells us the direction in which the particles in the exhaust plume are travelling, so to get the initial velocity vector for each particle, we take the ship velocity and add the exhaust vector (divided by 128). We then halve this value to get the velocity vector for the exhaust plume, so the particles travel at around half the velocity of the ship, in the direction of the plume, so they shoot out of the engine but soon get left behind as we blast away.

For the initial coordinates of each particle, we set them to the position of the player's ship, but a little way in the direction of the exhaust plume (so that's below the engine in the direction that it's pointing). We also subtract the velocity of the particle because the first thing that happens when we process the particle in MoveAndDrawParticles is to add the velocity, so this cancels that out to ensure the particle starts out along the line of the exhaust plume.

We finish off by calling AddExhaustParticleToBuffer the relevant number of times to add a cluster of exhaust particles to the start of the plume nearest the ship, with random elements added to give the particles a cloud-like effect as the exhaust plume fires off into the ether.

So that's how the flying model in Lander works, although whether this knowledge makes it easier to fly the ship is another matter altogether.